Green Infrastructure A Practical Guide for Cities and Communities

What Green Infrastructure Means Today

Green Infrastructure is a set of planning and design practices that use natural systems or mimic natural processes to manage water and improve urban environments. This approach includes parks and open spaces rain gardens green roofs street trees permeable pavements and restored wetlands that together provide multiple benefits for water management climate resilience and public health. For journalists policy makers and engaged citizens understanding the core ideas behind Green Infrastructure is essential for informed debate and effective action.

Why Green Infrastructure Matters

Cities face growing pressure from heavy rain events rising temperatures and aging gray systems that were built for a different era. Green Infrastructure reduces storm water runoff lowers urban heat and enhances air quality while also creating attractive public spaces that support biodiversity and local economies. These projects often cost less than traditional built solutions when long term benefits are considered. Green Infrastructure also strengthens community resilience by buffering neighborhoods from floods and heat waves and by providing places for recreation and social connection.

Core Types of Green Infrastructure

Common types include vegetated swales and bioswales that guide and filter runoff urban tree canopy and street tree plantings green roofs and roof gardens that retain water and reduce heat permeable pavements that let water soak into the soil urban wetlands and restored riversides parks and community gardens that absorb water and offer recreational value. Each option can be tailored to local climate soil conditions and community needs so planners can mix approaches for the greatest impact.

Design Principles for Successful Projects

Effective Green Infrastructure follows a few simple principles. First use natural processes to capture clean and retain water as close to its source as possible. Second integrate multifunctional design so that storm water benefits coexist with habitat shade and recreation. Third engage local communities from planning through maintenance so projects reflect local priorities and receive long term support. Fourth monitor performance to measure water quality improvements flow reduction and social benefits and adjust designs based on evidence.

Financing and Funding Models

Financing Green Infrastructure can draw on a wide array of public and private sources. Cities use utility fees grants impact fees and bonds to fund large scale projects. Private investment is growing as developers embrace low impact designs that reduce site costs and increase property value. Public private partnerships offer a flexible structure for funding multi actor projects. Conservation finance and green bonds are new tools that channel capital to projects that generate measurable environmental and social returns.

Policy Tools That Support Uptake

Policy plays a central role in mainstreaming Green Infrastructure. Updated design standards storm water codes and incentives for permeable surfaces can accelerate adoption. Local officials can require green storm water solutions in new development or offer fast track permitting for projects that meet environmental performance criteria. Research and reporting by reputable outlets increases public awareness and encourages political will. For regular coverage of how policy choices affect infrastructure and public life visit Politicxy.com to read analyses that connect politics with the built environment.

Community Engagement and Social Equity

Green Infrastructure should be equitable and inclusive. Projects that only appear in high income neighborhoods risk widening disparities in health and access to nature. Successful programs prioritize investments in underserved areas where storm water impacts and heat stress are most severe. Community led design builds ownership and ensures that public spaces meet local cultural and recreational needs. Workforce development linked to infrastructure projects can create jobs and training opportunities for local residents.

Measuring Success

Performance metrics are essential. Common measures include volume of runoff retained reduction in peak flows water quality improvements heat island mitigation tree canopy coverage and social indicators such as park usage and public satisfaction. Long term monitoring reveals how well systems perform over different seasons and under intense weather events. Data driven evaluation helps justify investment and guides replication at larger scales.

Overcoming Common Barriers

Barriers include budget constraints misaligned regulations lack of technical capacity and limited maintenance planning. Many municipal teams lack staff resources or experience with natural systems. Educational partnerships with universities and specialized consultants can close knowledge gaps. Flexible code reform and pilot projects help demonstrate feasibility and build political support. Maintenance agreements and community stewardship programs ensure that Green Infrastructure remains functional and beautiful for years to come.

Case Studies That Inspire

Examples from cities of all sizes show how Green Infrastructure can be adapted to diverse contexts. Small towns have implemented bioswale corridors to reduce flooding in main streets while large metropolitan areas have transformed brownfield sites into multifunctional parks that absorb storm water and attract visitors. Lessons from these projects emphasize incremental scaling use of native plants and strong partnerships between public agencies and community groups. For news updates research coverage and featured stories on environment and urban development visit newspapersio.com for timely reporting.

How To Start a Local Project

Begin by mapping local vulnerabilities and assets. Identify priority locations where runoff creates recurring problems or where heat stress affects vulnerable populations. Engage residents and local organizations to gather input and build a coalition. Seek funding for demonstration projects that provide clear examples of benefits. Use modular designs that can be scaled up over time. Document outcomes and share lessons with neighboring communities to foster wider adoption.

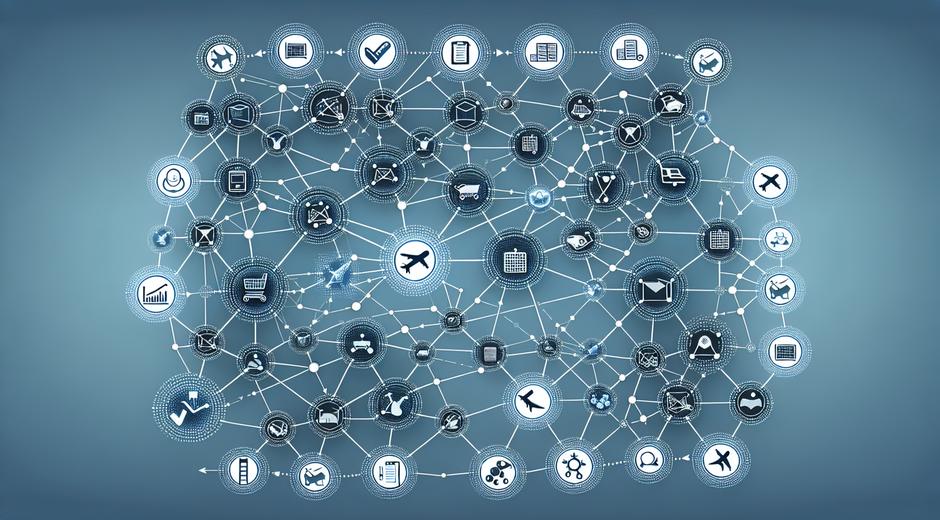

The Role of Technology and Innovation

New tools for data collection modeling and real time monitoring make it easier to design and manage Green Infrastructure. Remote sensing and geographic information systems allow planners to identify hotspots for intervention and to estimate potential benefits. Smart sensors embedded in soils and drains can trigger maintenance alerts and help optimize performance. While technology supports decisions it should complement not replace community input and ecological knowledge.

Looking Ahead

Green Infrastructure will play a pivotal role as cities adapt to changing climate patterns and growing populations. Integrating natural systems with engineered solutions creates flexible resilient urban landscapes that serve environmental public health and economic goals. As evidence mounts and best practices spread public investments are likely to grow and private actors will increasingly see value in green approaches. Effective communication by media outlets policy advocates and local leaders will be essential in maintaining momentum and ensuring that benefits reach all residents.

Conclusion

Green Infrastructure represents a practical pathway to healthier more resilient and more livable communities. By combining smart design thoughtful policy equitable investment and community engagement cities can transform vulnerabilities into opportunities. Ongoing reporting analysis and local success stories will keep the topic visible in public debate. For continuing coverage and background resources on environment policy and urban planning follow our reporting at newspapersio.com and consult expert commentary such as the analyses available at Politicxy.com when exploring the policy context.